High in the mountains of Tibet, 12,000 feet above sea level, a small spirit house stands alone on a wind-swept ledge. Inside, is a corpse, but a corpse like no other. Believed to be centuries old, it has never decayed. Locals worship him like a God, so who was he? What was his secret? Could it be true, as some locals say, that this man actually mummified himself.

An International group of scientists will try to uncover the truth. Their journey will reveal the strange power of meditation, secret rituals and the fine line between science and the supernatural. Professor Victor Mair, an anthropologist from the University of Pennsylvania and a renowned expert in Buddhism will lead a team including Professor Margaret Cox, a forensic anthropologist and Bruno Tonello the lead radiographer. The mummy is located close to one of the world’s most sensitive international regions – the border between India and China. Access to the site will be restricted and they will only have a few valuable hours to conduct their tests.

For a thousand years, Buddhist monks have gathered in these remote, inaccessible valleys to study the great wheel of rebirth and the art of dying. Ancient Tibetan manuscripts describe how they would tap into the long-lost secrets of the human mind.

The mummified body of this Tibetan man was discovered purely by chance, when two Indian border patrol officers were sent to repair a road, in the Spiti Valley, damaged by an earthquake.

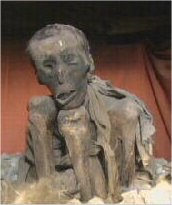

When the team finally reach the remote spirit house and see the mummy for the first time, they are amazed at how well preserved the body appears to be. All the more so, as there is no evidence of traditional embalming techniques.

The team are puzzled by the odd posture of the mummy and hope that X-Rays might help them decide if the position had been adopted before death, or post-mortem. The curvature of the spine and the general posture pointed to the life of a monk. Each day of that life would have begun with the chanting of the sacred texts, hour after hour they would recite religious verses, known as mantras. Even as a boy he would have learned to control his thoughts through simple meditation. But few monks would attempt to master the most powerful, the most dangerous Tibetan mental disciplines. Does the mummy’s severe posture suggest that he was pursuing these disciplines when he died? And what role did the strange fabric belt play?

Since ancient times, monks have used meditation cords, or belts to hold their bodies in difficult yogi positions. But the position of the mummy’s cord, around the neck, was very difficult to explain.

The team return to England to continue their tests in the laboratory, but Victor remain behind and visits one of the oldest sects of Tibetan Buddhism. The Nyingmapa are the guardians of the most secret forms of tantric meditation. He has a meeting with the Spiti Tulku, the spiritual Leader of the group and a master of tantric meditation. Victor asks him about the strange posture of the mummy and is told that the belt helps him maintain the sage posture, with the knees drawn up to the chest. The Tulku also suggests that the monk may have been practising one of the highest forms of mediation called zolk-shun. These advanced yogic postures also employed a meditation belt to free the body and travel deep into the mind. These techniques are believed to create immense physical power, so powerful and dangerous that a master would only pass them on verbally to one monk at a time. It is also said that a practitioner of zolk-shun can harness his mind in remarkable ways at the moment he dies.

In Boston, Dr. Herbert Benson of the Harvard Medical School is conducting experiments on Buddhist monks from Tibetan monasteries to asses the effects of meditation on the body’s metabolism. His research has provided a remarkable insight into the ways the mind can alter the functioning of the body. He has found that even with simple meditation, the monks can decrease their oxygen consumption by 60%. Monks practising Tumo, the yoga of inner heat, could increase their skin temperature to a point where, in an environment of 40°F and wrapped in ice-cold wet sheets, they could increase their body temperature to a level where the sheet would steam and dry out.

Victor considers the possibility that if the monks can dry an icy wet sheet with heat visualisation techniques, then maybe the mummy had sufficient power to do the same, but dry out his body.

Victor would finally fit the pieces of the puzzle together, not in Tibet, but in Japan. The Japanese Buddhist monks have long performed rituals of self-sacrifice to ease the burdens of their people. Tetsu Munki is venerated, to this day, for his extraordinary acts of suffering on behalf of his community. His 200 year old body is mummified in the local temple. Next, Victor travels to see the mummy of the revered Buki. His body, like that of the Tibetan monk, has been preserved without any embalming treatments. Local monks claim that he mummified himself. He starved himself by eating only tree bark and nuts, for three years. He climbed into a wooden box, where he meditated for days. As his life ebbed away, the box was buried. 60 years later, the box was reopened to reveal the mummy. It is believed that the fasting caused his internal organs and muscles to shrink, thus destroying the bacteria in his intestines. With no microbes to eat away at his corpse, Buki’s body was preserved.

Shortly after this, Victor receives news from England. The carbon 14 tests have revealed the Tibetan mummy dating back to the year 1475. Making it 500 years old, much older than the Japanese mummy. It also revealed high nitrogen levels suggesting the monk was extremely mal-nourished when he died. A fact that fits in with the theory of the Japanese mummy. Finally, Victor is to learn, that prior to the Chinese Cultural Revolution, there were hundreds of such mummies, but when the Chinese leaders ordered their desecration, the Tibetan people chose, instead, to cremate them